The mainstream media has come in for criticism from climate change experts over coverage of the spate of natural disasters to hit south Asia, the Caribbean and the south east of the US in 2017. Journalists were so careful to avoid concluding that such and such phenomenon was caused by manmade climate change that most managed to omit any mention of it whatsoever.

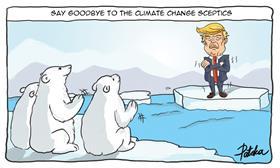

The arrival of climate change denier Donald Trump in the White House will have concerned many farmers, who depend upon accurate information on future climate trends to make sensible decisions for coming seasons. On this the Trump administration’s policies will not aid progress.

However, it is worth remembering that the US president’s “Chinese hoax” theory and speedy withdrawal from the Paris Agreement have done nothing to worsen the current state of the planet. And yet the problem is already here. The rise in sea temperatures, the rise in sea levels and the increase in moisture in the atmosphere did not begin in January 2017.

Change inevitable

“It’s a shame what Trump thinks, but it doesn’t matter,” says Volkert Engelsman, founder of Dutch organics and sustainability specialist Eosta. “Investors, insurance companies, multinationals – these are the ones that will drive change, and eventually they will force governments to act.”

Engelsman believes that serious action is becoming increasingly inevitable as climate change turns mainstream. “Climate change was once the concern of green idealistic circles,” he says. “Now it’s right at the fore for finance companies, investors, risk analysts and management consultants. Banks have always conducted financial stress tests, but now they do planetary stress tests too, as those that are exposed may be an investment or loan risk. Climate change threatens a company’s ability to make a profit once carbon taxes or other measures hit the market. And they will – the question is when. That is the reality.”

According to Engelsman, a major problem is the obsession with short-term productivity, which undermines the long-term ability to grow. “We need to move away from productivity as the only variable,” he says. “We are already blasting through the boundaries of our planet as identified by [environmental science professor] Johan Rockström. What we need is climate-smart agriculture, which means biodiversity-smart, water-smart and soil-smart. There’s an awareness war between short-term and long-term investors, but the long-term ones are finally starting to win.”

Flexible approach

The threat of climate change will also necessitate more flexible approaches to farming. Don Cameron, general manager of Californian produce grower Terranova Ranch, explains that growers in the state are already dealing with the effects of climate change.

“They might not have climate change in Washington, but we definitely have climate change in California,” he told a recent summit in London. “We didn’t have a pistachio crop a couple of years ago because there weren’t enough chill hours over winter. We’re seeing extreme heat, drought and extreme flooding.

“We are using groundwater recharge via flooding so we can make it through the drought. We’re also looking at different varieties of crops that can withstand different scenarios, and we’ve been trying to change our planting and harvesting patterns to take advantage of warmer temperatures.”

Large areas of east Africa, including swathes of Kenya, Somalia and Ethiopia, experienced severe droughts in 2017. In Kenya, basics like corn are rapidly becoming luxuries, while 3.4 million Kenyans now require urgent food assistance. In Egypt, where water is far less scarce, growers are equally trying to remain flexible to the changing local conditions. “One of the biggest future challenges for us is in adapting to climate change,” says Hassan Zaher of exporter Ghabbour Farms. “You’re seeing hurricanes, storms, fires and floods become more frequent. The weather is the most important factor at the moment, more important than varieties or markets. We are looking at any product that grows well in the local environment.”

“We’ve met plenty of farmers changing their ways,” Engelsman agrees, “especially in dry places like Namibia, South Africa, China and Argentina. You used to see farmers in these places getting rid of all the weeds with glyphosate. Now you see people cutting back on their use of mineral fertilisers, which are expensive and deplete your soil or leak into the groundwater and atmosphere. It is easier to handle droughts and floods when you have healthy soils. In Orange River, in southern Namibia, the heatwaves are destroying farmers’ crops, so they are looking at alternative products to grow.”

Reducing dependence

While some are looking at the possibility of producing different crops to better suit the prevailing conditions, others are searching elsewhere for the necessary resources. An Abu Dhabi-based eco-firm plans to tow icebergs to the UAE from Antarctica in early 2018 to harvest the ice for pure drinking water. The news has prompted drought-affected South Africa to consider a similar move for its farmers. The presence of giant icebergs off the coast of the UAE might even create new micro-climates that could bring more rain to this arid landscape, facilitating the country’s efforts to increase its own food independence.

The fact is that in much of the world, rising temperatures, water scarcity and more regular extreme weather events will make food production more difficult, pushing those reliant on imports into an increasingly precarious predicament. For the UK’s Soil Association, it is necessary not only to invest in more resilient farming systems, but also to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture, pointing to organic as the solution.

Organic solution

Organic farms emit fewer greenhouse gases and use less energy than conventional farms, while sustainably managed soils store up to 450kg more carbon per hectare and leach 35-65 per cent less nitrogen, says the Soil Association’s Honor Eldridge. Converting half of EU land to organics by 2030 would cut agricultural emissions by around 23 per cent, according to IFOAM and the Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FIBL).

“Through crop diversification, agroforestry and integrated livestock management systems, we can help to create more climate-resilient systems,” says Eldridge. “Management of soil fertility through rotations, cover crops and manuring can increase water retention in soil and offer a better response to droughts and floods and reduce the need for irrigation.”

Beyond awareness

Despite efforts by some to obfuscate the dangers ahead – the most cynical being the Trump team’s removal of the phrase “climate change” from the Environmental Protection Agency website – knowledge of the threat will only grow in the future as the effects become increasingly apparent. The Syrian refugee crisis is just one example, beginning as it did with the displacement of hundreds of thousands fleeing drought in the south. Meanwhile, a combination of climate change and widespread pesticide use is believed to be responsible for the collapse in pollinator numbers. However, according to Engelsman, making real change will take more than just awareness.

“If you want to deliver change, you need to co-create, which is a social challenge,” he says. “That requires a shift in consciousness. There is a systemic failure in our economic system, and we desperately need new ways of thinking. There’s nothing wrong with profit, but not at the expense of people and planet. This is where true cost accounting comes in.”

True cost accounting is a means of calculating a product’s overall cost, including its impact on health, climate, water quality and soil erosion. A 2017 study by Eosta found that its organic apples were in fact €0.19 cheaper per kilo than their conventional counterparts when external costs were taken into account.

Part of Engelsman’s motivation stems from his belief that the agriculture sector has a particular duty to act on climate change. “Agriculture plays a major role in terms of greenhouse gas emissions and biodiversity loss, so we have a major responsibility to act,” he says. “But it is also a huge commercial opportunity to compete not just on price, but also on health, the environment and social responsibility.”