Always on the lookout for reliable and industrious farm workers, the salad growers sector could soon be employing a whole army of tiny helpers in the battle against pests.

Research now being carried out at Yorkshire’s Stockbridge Technology Centre (STC) is exploring how growers can harness the power of insects to reduce levels of pesticide use.

The project aims to build on years of experience in the glasshouse sector, using predator insects like ladybirds and lacewings to feed on pests, extending the basic principles to the outdoor farm site. Stockbridge has joined-up with researchers at York’s Central Science Laboratory and Lancaster University, who have been working on this idea for several years, focusing particularly on brassica growers in the Netherlands. It may resemble mere field margins, but the level of detail the research involves far exceeds that.

“Work done by Felix Wackers with Lancaster University suggests that out of 20 flowers generally included in a wildflower mix, only four actually encourage beneficials,” STC entomologist Pat Croft notes.

“This means we have to be very much more targeted in our approach, considering the particular pests attracted by different crops and then which predator or parasitoid we want to encourage.”

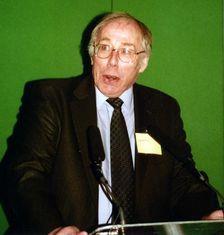

Stcokbridge chief executive Graham Ward is upbeat about the project’s prospects. “This really moves the argument on in leaps and bounds,” he says. “We are looking in much more detail at what we mean by sustainable farming and how we can use environmental measures to actually help us grow our crops with fewer pesticide sprays and so create a real point of difference for UK produce, as against produce grown in warmer climes, where this concept is simply not viable. Our goal is to take a ‘whole farm’ approach and effectively change the ecology of the farm. This is important, partly because the challenge is far greater for vulnerable vegetable and salad crops.”

The key challenge researchers must answer lies in manipulating their behaviour to get them to move into the crop on demand. This can involve the use of pheromones or plant volatiles - chemicals released by plants as they come under attack.

As a result, the trial established by Stockbridge staff - currently over three fields and a total of 17 acres - has involved planting 1.8 metre wide wildflower strips around the fields. These were planted last year, along with shrubs, hedging plants and trees to provide a variety of habitats, supplemented with further features such as beetle banks.

With three crops now introduced - peas, potatoes and lettuce - the challenge is on to fine-tune the wildflower borders to get the right balance of predator and parasitoid insects. The team is also looking at methods of supplementing the population if needs be.

Ward thinks it may be three or four years before the research is sufficiently advanced that growers will be able to benefit directly from its findings. But, he argues, the impact of reducing our dependence on pesticides could be phenomenal.