The Wimbledon tennis championships are due to start in a couple of weeks, which means British strawberries are very much on Centre Court again. And while the traditions observed in SW19 during the first half of July have hardly changed over the past few decades, the industry behind its favourite fresh fruit treat certainly has. What’s more, there is a new revolution set to start, one that will see the fruit grown, harvested and sold in dramatically different ways.

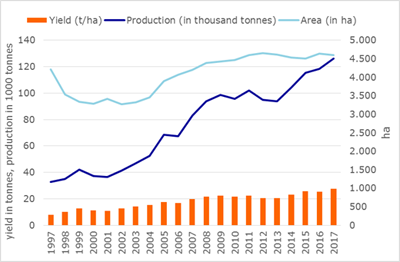

While the area used to grow strawberries in the UK has only shown a modest increase, production volumes have grown enormously. In 1997, when Pete Sampras was still dominating Wimbledon, UK strawberry production totalled roughly 33,000 tonnes, with a similar volume of fresh strawberries imported. Twenty years later, UK production was over 120,000 tonnes, while imports stood at 58,000 tonnes.

With a good harvest also likely this year following recent warm weather, that increase in supply and imports comes in the wake of spectacular growth in strawberry demand over the last few years. In 2017, the market grew by a stunning 8 per cent. If the crop continues to grow well and consequently prices remain at attractive levels (for consumers), then 2018 could be another record year for the British strawberry market.

From a more structural standpoint, UK strawberry growers have been able to boost their production by using polytunnels and new varieties. Other advances include production in glasshouses and in grow bags – made from coconut coir or peat – on table tops. These advances don’t just extend the season and increase yields: they are also very important because of the higher consistency they bring in terms of both availability and quality. Furthermore, the use of chemical crop protection is substantially reduced if fields are covered. Increasingly important, meanwhile, is the improvement as far as labour is concerned: with the use of table tops and coverings, fruit pickers do not have to squat or bend over; plus, they have shelter from the rain.

Strawberries have always been a typical UK product. Although the share fluctuates from year to year, around two-thirds of all strawberries consumed in the UK are produced domestically. In summertime, nearly all strawberries are British. For comparison: less than 20 per cent of the tomatoes consumed in the UK are home grown. Three months – March, April and May – account for over half of the country’s annual strawberry import volumes, with most coming from Spain. This has remained pretty stable over the last five years, although autumn imports from the Netherlands and Belgium have risen notably, driven by major investments in Dutch glasshouse production.

Now that over 90 per cent of British production is covered by polytunnels, the first revolution in UK strawberry production has almost come to an end. But another strawberry revolution has just started. As is the case across north-west Europe, the UK’s strawberry production is expected to move increasingly out of the soil. Even more revolutionary will be the use of picking robots. It is inevitable that this kind of automation will be used in the long term as the availability of labour is running dry. This applies not only to the UK, which might be hit hardest by a lack of labour because of Brexit, but even to countries like Poland, which now face a similar challenge.

Elsewhere, another challenge is the war on plastics. After a wave of plastic packaging innovation in the berry industry, which has resulted in more convenience for consumers and longer shelf-life for the berries, the tide is going to turn. As a result, the berry industry might be forced to return to more expensive and less convenient alternatives.

Despite all these major changes, spectators at Wimbledon – and why not those watching the football World Cup? – will continue to eat British strawberries. However, they might well become more expensive in the coming years and be harvested by machines, instead of people.