Consumer lifestyle solutions are fast becoming a powerful vehicle for the large UK multiples to develop into brands and of themselves.

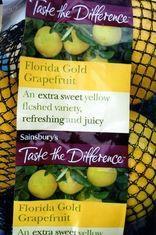

The immediate impact of this change has been a revival of the private label - own label sales of packaged food grew by £438 million in 2001 following several years of steady and slow decline. Premium ranges including the successful Taste the Difference range from Sainsbury’s and the quick expansion of Tesco Finest, along with Organic ranges from both retailers, have added value. Division of own labels into the three or more lines - value, Me-2 and luxury for example - has expanded the repertoire from one retailer brand to several sub-brands that cover the full spectrum of consumer needs, from budget to gourmet to organic, special dietary needs, and more recently to convenience lines with the launch of Just Cook by Sainsbury’s this year.

According to retail consultant and ex-Tesco head of private label development Christine Cross, the value of the sub-brand is in the demographic that it attracts to stores, it also differentiates the retailer from its competitors, and encourages loyalty among a valuable demographic. Cross headed Tesco’s private label development from 1989 to 1995 before moving across to category management. “Development of private label was part of Tesco’s total brand strategy and the entire brand positioning work was done in-house. There is a distinction between a private label and an own-brand. Initially, private labels meant going through a buying group or taking on a limited distribution of a tertiary brand, which gave you a point of difference and some margin advantage.

“However, to develop an own brand it meant developing a brand strategy, deciding on the quality of the product, matching the range to your customer and your commercial proposition. Ultimately own brand delivers customer loyalty because they develop a trust in the produce and allows the retailer to diversify between categories.” Cross explains that this is how Tesco started with ambient grocery, then moved to chilled and so on. “This strategy allows translation across product boundaries because customers learn to trust their own brand,” he says.

Tesco had a private label in grocery that tended to be entry price-point products in the early 1980s or branded Me-2s. “Tesco had a heritage in it so it was the obvious category to start with and correct. In the late 80s and early 90s, the three pillar brands were developed over time starting with the Tesco standard proposition. This involved matching key branded players.

In 1992 the value proposition was introduced to compete with discounters, such as Costco, into the UK. The third pillar was the finest proposition, where the aim is not to match another branded product but to stretch quality and price propositions, offering best in class. These lines compete against specialists and offer something uniquely different,” Cross says.

Unlike the US model, all lines for UK retailers were mainly developed in house by product development teams. Cross says: “This model changed in mid 90s when category management was introduced and the new private development team moved into the category. In the UK, private labels have become more own brand while in the US there is not a discreet brand strategy. In the UK, the own brand strategy for Tesco is very different to Waitrose and Sainsbury.”

According to Cross, all three own-label categories will continue to grow. “Currently own-label penetration for Tesco is 60 per cent of volume through the store, split between the three classes. All lines will always be there and change depending on the economic circumstance, where you will sell more value or more finest, depending on the store. The proposition will be mixed differently from store to store, for example some Metro stores in London stock more finest and less value while others stock more value and less Finest.”

Similarly, Sainsbury’s Taste the Difference range appeals to a group of food-aware consumers who fill their trolleys with premium products. Currently one third of Sainsbury’s shoppers buy from the Taste the Difference label on a weekly basis. Because of an evolving own-label strategy from retailers, Tesco Finest and Sainsbury’s Taste the Difference have already developed a level of recognition comparable to many of the UK’s top brands. Sainsbury’s Taste the Difference was worth an estimated £350m in retail sales in 2002 and Tesco’s Finest was even larger, generating almost £500m. Sainsbury’s Taste the Difference range was almost one and a half times the size of Mars including Mars Ice Cream and Mars dairy drinks.

Today almost every retailer considers their own label programme to be a strategic necessity, says president of the Private Label Marketing Association Brian Sharoff. “This is true whether we speak of countries with very high own label penetration such as the UK or countries with lower own label share such as Spain or Austria. Retailers may differ on how to implement the strategy, but share recognition of its overall significance to their profits, image and future growth,” says Sharoff.

“The question of own label in fresh produce is tied to the entire issue of whether produce can be successfully branded in the first place. Several retailers, notably in the UK, have pioneered in own label produce. Retailers in other countries have been less aggressive, partly out of reluctance to deal with the additional procurement and management requirements that an own-label programme imposes.

“I think a more influential factor has been the changes in consumer attitudes toward the produce that shoppers now buy. They are looking for greater variety than ever before as well as portion sizes that reflect their eating needs. This, in turn, has opened the door to retailers to use their own label to satisfy consumer desires,” he says.

“Today, there is a larger trend towards offering consumers convenience foods in stores and we have seen the expansion of the ready meal in terms of availability and convenience. Some UK retailers now provide all the fresh ingredients for a meal, bringing more fresh produce into their own lines. This is in response to consumers developing tastes for new cuisines and a wider demand for fresh foods in stores.”

According to PLMA research manager Jeff Freeman, own labels have several advantages for retailers; they help to build brand loyalty from shoppers and project the store name of the product; they offer a unique product to consumers and reinforce the store identity; they are good for store sales as they allow the whole store to be promoted, and allow for co-branding. “In the fresh produce sector, the retailer would negotiate with the grower on quantity and price, but not on marketing. For example UK apples grown for a co-op are branded under the Tesco Finest or Organic lines, which is co-branding; UK apples and Tesco.”

Freeman adds that own brands help to retain customers and help retailers with their trading positions such as online sales. “Own labels have evolved,” explains Freeman. “Recently 3G own labels have emerged such as Tesco’s Finest, offering consumers high-end value-added lines which have no branded competition.”

According to the PLMA, the main catalyst for own label growth in Europe has been the consolidation of supermarkets who understand the need for developing own brands. The PLMA’s annual statistical yearbook, based on ACNielsen data ranked the UK higher than other European countries in terms of both volume and value. Sharoff thinks this ranking reflects time, because UK retailers started their Own-label programmes earlier. “The slower pace among other European countries relates to the fragmentation of their retail markets, which only began to reorganise themselves over the last 10 years,” he says. “Certainly, consumer attitudes are something to do with it and many Europeans have become used to the lure of hard discounters, which in turn skews purchasing habits toward low price rather than innovative, higher quality own label, which is the norm in the UK.”

For the future, own labelling is expected to continue to grow and multiples will develop their own own labels at the expense of brand labelled products. Apart from price driven own labels, the upmarket label will mainly develop - this has already been achieved in the UK with such products as Marks & Spencer sandwiches - and own labels will continue to compete with brand leaders. With respect to the UK fresh produce sector, Sharoff says own labels are well established. The PLMA’s annual statistical yearbook documents own label market share for fresh produce at more than 60 per cent by volume and over 50 per cent by value. “In other European markets, ACNielsen is not able to provide comparable statistics so one must rely on visits to stores for trends,” he says. “Supermarkets and hypermarkets in France, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Spain appear well on their way to developing produce as a part of their overall own label strategy. It will take several years for retailers to match the UK but the beginnings of the process are underway.”

The next battleground will be in fresh, says Cross. “This has been started off with bagged salads and fruit salad. This category will be the focus to make customers recognise them as own brand. The next opportunity will be to move across all fresh produce. If you think of loose fruit and vegetables, there is very little brand recognition there; people know the varieties, except for perhaps Fyffes bananas or Outspan oranges. If we can get consumers to think of other produce as Tesco brand, then recognition is stretched as is the reason to purchase, by associating good quality produce and loyalty. The more bespoke information you can put on a product such as traceability, serving suggestions, and nutritional benefits all help branding the product as the store’s own.

“Fresh produce is the only battleground left. It is a challenge with loose produce - you would need point of sale information such as header boards above the produce, educational leaflets passing information back to the consumers.” The consumer drives line development, in particular with convenience products today. Retailers are trying to expand their fresh and added value lines but the key constrain is the supplier base. Bagged salads now dominate over whole lettuce, and the next sector will be prepared fruit. You can see some of the development in M&S with ready to cook or steam packs with prepared vegetables. But once it is in one segment then consumers demand it in others.”