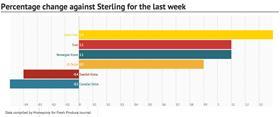

It was plain to see why the Swiss Franc and the Euro took the week's two top slots, scoring 1.4 and 1.1 per cent percentage changes against Sterling.

They used the simple expedient of keeping their heads below the parapet.

Other than German investor sentiment, which was not particularly buoyant, there were no highly-important Euroland economic statistics and there were none at all from Switzerland.

The Norwegian Krone was more deserving of its leading position; Norway's trade surplus in January was the biggest ever.

Sterling's week was spoiled by a below-forecast UK inflation figure. Instead of the 2 per cent that investors had been expecting, consumer prices rose by only 1.9 per cent in the year to January. While there is hardly a big difference between 2 per cent and 1.9 per cent, investors suddenly realised that UK inflation was not bound to stop when it reached its target. It could possibly continue falling, putting back the day when the Bank of England needs to begin raising interest rates.

There was not the usual negative correlation that sends commodity-oriented and safe-haven currencies in opposite directions. The Australian Dollar and the Japanese Yen delivered almost identical performances. Canada's Dollar was the weakest of the lot, falling by nearly a cent against Sterling. It took a dive when its value against the US Dollar was pushed below technical support. The pretext for the selling was a disappointing figure for Canadian wholesale sales, not usually a statistic that moves the currency. Investors were apparently spoiling for another fight with the 'Loonie' and seized upon the first excuse that cropped up.

The highest-profile events on this week's agenda are Wednesday's revision to fourth quarter UK growth and Friday's provisional Eurozone inflation figures. The former is emotive beyond its real historical importance. The latter will be an serious consideration for the European Central Bank's governing council when it meets in ten days' time to decide whether or not to relax monetary policy.