You could be forgiven for thinking that things have changed irrevocably in the fresh produce industry since the freshly minted Fruit, Vegetables and Flower Trades Journal hit the industry’s desks in 1895. And of course, in many respects it has. But although we may be 110 years down the line, the underlying issues that the editorial team found the industry facing in 1895 are not that far removed from those we report on today.

Grappling with a rising tide of imported produce as they neared the 20th century, the UK’s domestic fresh produce industry believed it was struggling to maintain its place in a rapidly changing world.

The Journal was created out of a necessity to raise awareness of these issues, share ideas and information and influence national policy.

The early years of the publication’s life, from 1895 to the beginning of World War I in 1914, were dominated by the fear of imports and the problems facing the UK grower base, yet while the Journal remained sympathetic to the industry’s plight its support was balanced by a recognition for the need to welcome overseas products to meet consumer needs.

At the time, the over-riding editorial stance was to be critical of importing products that could be effectively grown at home, whilst simultaneously recognising the advantages of importing out-of-season lines to ensure the market was supplied with the widest selection of products, for the longest possible period, at the lowest possible price. While oceans of water have passed under that particular bridge, and continue to, the Journal has never shifted away from that editorial position.

The tail end of the 19th century witnessed considerable change in the industry, and the establishment of steam shipping and extensive railway networks saw an increasing range of fruit and vegetable products arriving on the UK market.

At the time, the principal points of entry were London, Liverpool and Hull and these cities all had their own distinctive markets.

Covent Garden supplied London and much of the south, either directly or via its satellite markets, and competed with Liverpool for trade in the Midlands.

At the time of the Journal’s arrival, London and Liverpool were already starting to handle imports from Australasia, Brazil, Canada, the Canary Islands, the Mediterranean, Portugal, Spain, the West Indies, the US and early trade from South Africa.

At the same time, the new publication reported that exotic crops were beginning to arrive on the market, such as the banana, which was imported from the Canaries and Madeira, along with lychees and prickly pears.

While these imports were on the rise, the development of technology to aid cooling and refrigeration was still in its infancy and large-scale volume was still a distant dream.

By 1895, internal logistics for the UK market was handled by around 20,000 miles of private railway network, which provided major links between the ports of production areas and their markets in the growing towns and cities.

Transport from the surrounding areas into city centres and from the markets themselves was by road, relying primarily on animal power.

The slow speed of horse-driven distribution meant the fruit and veg trade was quick to show an interest in the development of motor transport and early reports in the Journal focused on the exciting new developments and possibilities being opened up by motor vehicles. The reduction in costs saw the rapid expansion of road transport and by 1914, motor vehicles were effectively competing with the railways.

In the last years of Victorian Britain, the development of the banana business took up an ever-increasing proportion of the early Journal column inches. The pioneer of this trade was Sir Alfred Jones who quickly identified that a large market existed for both bananas and tomatoes from the Canary Islands.

Sir Alfred quickly established a technique to ensure bananas arrived in the market without over-ripening and while the developments incurred considerable cost, he saw the business expand from 10,000 bunches in 1884 to more than 1.5 million in 1900.

This success encouraged other businessmen and led to Eward Walthen Fyffe, a London tea importer, establishing an agency in London for potential banana growers. In 1901 Fyffe joined forces with Sir Alfred’s company, Elder Dempster, to create Elders and Fyffes Ltd.

Further development, following government prompting, saw the new business innovate further to allow the shipment of bananas from Jamaica and that new technology paved the way for our modern global business, allowing shipments of all manner of fruit and veg from around the world.

For the independent retailers, the biggest challenge during the Journal’s early years involved hygiene and short weights, with many a businessmen being fined for dodgy practices. The Journal warned its readers: “It behoves retailers to be very, very careful when food inspectors are on the prowl.”

The Great War of 1914-1918 initially had little impact on the sector with the government adopting a “business as usual” attitude for the first two years.

However, the increasing requisition of merchant ships, not to mention their sinking, forced a change of attitude. Rationing was introduced on some core staple products, but the hostilities, perhaps perversely, provided a shot in the arm for the depressed domestic growing base. Consumption of home-grown fruit and vegetables rose dramatically as the import routes were cut off.

The Journal played a full role during the war, publishing any and all government regulations which affected the sector, while promoting domestic consumption.

In 1916 the publication celebrated its 21st birthday and the editor wrote: “For the first few years it was uphill work, the trade continuing to pursue that policy of secrecy for which it has always been noted.”

The end of hostilities saw little government support offered to UK agriculture, a fact lamented by the editor of the time, and once again, overseas imports began to bite back into the domestic sector’s share.

While the market for fruit and vegetables was on the rise, the industry recognised the need to continue to push forward, and to this end, in 1920, the Imperial Fruit Show was established, an event that was quickly to become the highlight of the social calendar. This in turn led to other initiatives, most notably a major advertising campaign in 1923, using the slogan “Eat More Fruit”, which was funded by levy payments.

The success of the industry’s first generic scheme was astounding. The Journal reported that fruit consumption increased by £1m in the first year and £2m in the second year. The success of this scheme led to an increase in the use of brands with Fyffes Blue Label, Pagoda Oranges and Jaffa Oranges among the most notable names to emerge.

The death knell of the UK’s free-market status was sounded by the collapse of the US economy with the Wall Street crash in 1929. By 1932 tariffs and quotas had been introduced and numerous marketing and subsidy schemes launched to support domestic production. The adoption of the Empire Preference in 1932 also shifted the focus of imports away from foreign countries and towards Britain’s dominions, colonies and protectorates. An article in the Journal illustrates the effect of this move, showing Jamaican bananas’ market share jumping from 26 per cent in the 1920s to 87 per cent in 1937.

Further market changes were witnessed in the inter-war years, most notably the introduction of the first air-freighted fruit in 1919 carried by Flying Transport Ltd, which operated a service between Paris and London. The Journal reported that one Covent Garden firm, Messrs Charles Wilkinson, was the first to air-freight strawberries from Paris. Flowers from Holland were quick to follow the trend and by the late 1930s this became a substantial business.

Not to be left behind, the rail business was given a boost with the establishment of train-ferries to cater for goods wagons. This opened up transport routes throughout Europe.

While logistics were improving beyond compare, the structure of the UK industry changed little in the inter-war years, with importers and growers supplying the wholesalers, which, in turn, supplied the retailers.

Covent Garden, although becoming increasingly inconvenient as the metropolis of London sprouted around it, remained the principal centre, with Borough, Brentford, Greenwich, Spitalfields and Stratford playing supporting roles in the capital city. However, within the pages of the ever-present Journal, there was a sign of things to come in the retail sector as the likes of J Sainsbury showed impressive expansion figures.

The Second World War (1939-45) again saw a significant rise in home production, boosted by the Dig for Victory campaign and the hard work of the landgirls, school children and even prisoners-of-war. Vegetable production rose 45 per cent and potatoes 87 per cent. While production rose, however, fruit production was unable to match the fall in imports and consumers during war-time experienced a “fruit famine”.

Many men and women from the fruit and vegetable industries lost their lives in the war, both on the battlefields and back at home. Covent Garden was badly damaged by bombs, while 115 people were killed by flying bombs at Smithfield Market. As in the Great War, the Journal acted on behalf of the government to help disseminate information to the trade. The commitment of the Journal staff to the cause, and the will to carry out its role regardless of the obstacles, meant that the publication can make the rare claim that not one issue was missed during either of the lengthy conflicts.

The government ban on bananas during the war years was ended with the arrival of Fyffes’ SS Tilapa containing 10m bananas, ushering in a new era of plenty, (certainly on bananas). However, it was not until 1955 that the pre-war levels of 305,000 tonnes could be reached, the Journal reported.

Post-war confusion in the trade led to supply disruption and this prompted the government to create the Fruit and Vegetable Organisation, which was designed to bring fresh produce to the consumer at the lowest possible cost. In spite of the organisation’s good intentions it was widely regarded as a failure by the industry, although it did help to promote a greater level of co-operation within the trade according to some.

The ongoing battle for distribution rights saw road transport gain the upper-hand over rail, with a significant turning point being Geest’s decision, in the 1960s, to replace its railfeight business with articulated container lorries. While the airlines were nationalised in the post-war years, a private industry sprang up on a charter basis and soft-fruit was soon being transported from places such as Italy by converted Lancaster and Halifax bombers. The success of such services was dubious, commercially, but it did not deter more experimentation, with flying boats being used at one point. The Journal noted, in 1949, that around six tonnes of apricots were flown in this manner from Spain to Southampton.

Despite all this, the majority of produce from Europe was brought in by sea, and shipping lines continued to flourish. While Liverpool and London remained the major docking points, smaller port towns began to make their presence felt, such as Dover, Boston, Portsmouth, Sharpness and Shoreham. The development of multi-temperature shipping meant vessels were now able to carry a mixed cargo, increasing flexibility.

Imports took a while to re-establish themselves, but gradually began to rise and soon reached new levels, with major increases in apples, pears, citrus and grapes, along with some rises in stone fruit, soft fruit and nuts.

Vegetable imports also began to climb again with broccoli, cauliflowers, onions and potatoes rising significantly.

Government control on supply slowly ebbed away so that by the end of the 1950s, only bananas and potatoes were subject to direct regulation. The reduction of emphasis on seasonality, while by no means having disappeared at this stage, can be traced to this point, as consumption of fruit and veg began to largely be dictated by the laws of supply and demand.

According to figures from the Journal, the changing market saw the consumption of fruit rise significantly, from 104lbs a head in 1938 to 149lbs in 1960. However consumption of fresh vegetables fell from 127lbs to 107lbs per capita in the same period. Total imports of fresh produce had risen to more than £237m.

The Horticultural Bill of 1963 received a lot of attention in the Journal pages. It offered aid under a grant scheme, including funds for the rebuilding of wholesale markets, sparking a major redevelopment phase for many of the UK’s trading centres.

The Bill also established a compulsory quality-grading scheme for fresh produce.

The UK’s entry into the European Economic Community in 1973 was another milestone that would have far-reaching effects on the industry. While the Journal recorded that initial reaction to the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) was positive, the mood quickly changed - reform of the CAP is an issue that still resonates today, although the fresh produce sector has long since accepted that it is not top of the list when EU monies are handed out.

1974 saw the move of Covent Garden Market from congested central London to Nine Elms, and was just one example of the modernisation of the wholesale markets.

However, the Journal highlighted the growing threat to the sector from the rise of the supermarkets, which were, by the early 1980s, bypassing the markets to source their own produce and gaining an ever-greater share of the market.

Reader unrest was registered in the early days of the supermarkets, as the Journal’s bedrock of wholesale markets and independent retail readership began to see its overall influence on the industry eroded. Some said the Journal should ignore the supermarkets altogether - but in the interest of providing its readers with the complete picture, these demands were given short shrift.

The emergence of marketing board organisations had also begun to reshape the industry and by the early 1970s, much of the imported apples and pears and citrus sector was controlled by such boards.

The 1970s and much of the 1980s were mainly marked by the serious problem of inflation, and the depressed economy which was inevitably created as a result. This led to a number of high-profile bankruptcies and voluntary liquidations, all sadly recorded in the pages of the Journal.

The Journal has prided itself as being at the vanguard of industry developments. A perpetual feature has been our unrivalled weekly coverage of national markets and wholesale prices, a continuation of the early market reports that date all the way back to 1895. The Journal has also followed closely the impact of technology, not just on the industry, but on the publication itself. Lockwood Press was quick to see the potential of computers and was among the first weekly publications to move to desktop publishing in the 1980s.

Rail transport continued to suffer under the competition from road, and the roll-on/roll-off ferries and developments in container transport added to the sector’s misery. However, when plans were announced for the Channel Tunnel, a new challenge was posed to the ferry industry. The transition from reefer shipping to containers was gathering pace, and a greater emphasis was placed on transportation methods that reduced handling and quickened turn-around times and the concept of a cool-chain began to take shape. Advances in airfreight have also been significant and charted over the last 30 years.

The beginning of the banana wars in the early 90s were heavily covered by the publication, and the ongoing political manoeuvring which surrounds the UK’s favourite fruit still rumbles on.

1992 saw the formation of the Fresh Produce Consortium, a new over-arching trade association to represent all strands of the industry. Chief executive Doug Henderson served the association for 12 years before handing over the reins to Nigel Jenney. Henderson increased the profile of the UK at international events immeasurably and ushered in a new century by cementing relations with fruit and vegetable industries around the world. Attempts to get a generic promotion campaign off the ground in the late 1990s twice foundered because the required cash could not be raised from the industry. Jenney is hopeful that it will be third time lucky for the FPC in 2005.

The publication in 1994 of the Strathclyde Report on the wholesale market sector brought about a seachange in the recognition of that section of the trade that its days as the market shapers were numbered. The report suggested that a serious cull of wholesaler numbers was the only way the industry could sustain itself in the long-term, and economic and natural factors have combined to ensure that this has happened.

By 1995, when the Fresh Produce Journal celebrated a century of providing the industry with its weekly news, the structure of the market had changed beyond all recognition, and the supermarket sector was well into its inexorable march to market domination. The Journal noted that the market was worth £3.4bn and a total of 6.8m tonnes of fresh produce was being consumed a year by the British public. The wholesale market role was diminishing, but traders still handled around 40 per cent of the countries fruit and veg.

In 2005, the picture has changed again. While popular opinion has it that the supermarkets represent 80 per cent of the market, it is way off the mark. The supermarkets sell just over 50 per cent of the fresh produce that finds its way onto the UK marketplace. The country’s wholesalers, inside and outside of the markets, have been boosted by the surge in growth of the foodservice sector and the trend for consumers to eat more out-of-home, and helped along by a more realistic adaptation to the needs of the 21st century commercial environment, still retain around 35 per cent of the fruit and vegetable sales. Balance has been restored and the harbingers of doom for the wholesale trade have moved on to pastures new. The foodservice sector, which partly overlaps with the wholesale sector figures of course, can claim more than 30 per cent of fruit and vegetable sales in the UK. Moves to source fresh produce direct have been stepped up, after the fragmented nature of the sector and a general lack of fresh produce expertise held its procurement ability back as the boom took place.

As the industry moved into the new millennium the Journal continued to reflect the changing face of the sector, reporting extensively on the demise of the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAFF) and its replacement with the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). However, in general, horticulture has continued to remain outside the main political stream.

The enlargement of the EU eastwards is something the industry, and the Journal keeps an eye on, but we are still waiting to see the long-term effect the expansion will have on the sector. Free-trade agreements and deregulation of some of the key supply markets have had their effect too, and political and economic factors, alongside tremendous technological advances, have created a market that has never been more competitive, or price conscious.

Consequently, the last few years of category management, supplier rationalisation, spiralling costs and diminishing returns have proved something of a roller-coaster ride, with government intervention failing to check the seemingly unquenchable ambition of some of the retail giants.

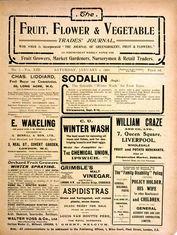

The Journal has come in 16 different guises over its 110-year history, with name changes and re-designs reflecting its desire to remain contemporary and relevant. While the readership profile has changed with the industry, our editorial policy and relationship the industry has remained simple - we are here to report impartially and independently on the global fresh produce industry with a distinctly UK perspective. With a 17th new era dawning for the FPJ, we look forward to reflecting the travails of the industry for a long time to come.

JUSTIN HOPE-MASON, MD LOCKWOOD PRESS LTD

“In pursuance with our announcement in last week’s issue, we now present this Journal in an altered form, which we feel sure will meet with the approval of the readers.”

So wrote my great-grandfather, Harvey H. Mason in the “Fruit, Flower & Vegetable Trades’ Journal 70 years ago. In the same article, he referred to the first issue published under his stewardship, on 22 June 1907 which included a manifesto pledge from the new proprietor: “Realising that few, if any, industries in the United Kingdom are beset with a greater number of anomalies or faced with more difficult problems, it will be the object of the new proprietorship to get behind these difficulties in an endeavour to smooth out the rough places and tone down conflicting interests.”

Since our first issue in October 1895, the Journal has undergone around 14 major redesigns to the masthead, and a few other more minor adjustments to its appearance inside. The title changed to the Fruit Trades Journal in October 1970, and became the Fresh Produce Journal in March 1989. In order to emphasise our focus on up-to-date industry news, the front cover carried the leading news stories for the first time in January 1991.

Since then, we have continued to update the appearance to ensure the Journal maintains a modern, fresh and easy to use look and feel. Our most recent major redesign was in 1999 and coincided with the launch of our industry leading website www.freshinfo.com. In today’s fast moving industry, and with the parallel rapid changes in publishing technology, the Journal was long overdue an update. As this month marks the passing of our 110th year of continuous publication, we have taken this opportunity to coincide this milestone with our latest redesign.

The Journal you are now holding started life in March of this year when we started discussing what we wanted from a new look Fresh Produce Journal. Our two most important questions were a) should we change size to A4, and b) Should we re-brand ourselves as the FPJ?

The results you can see for yourself. The FPJ is the industry’s newspaper first and foremost, and despite the current fashion among broadsheet daily newspapers to downsize to tabloid, the same arguments for resizing cannot be applied here. We are not competing for hassled commuters making an impulse buy. We are presenting reasoned industry news in a form that is quick and easy to access, and a change for the sake of it would do nothing to enhance the title.

Secondly, we are referred to as the FPJ more often than the Fresh Produce Journal by everyone almost without exception - indeed we are still referred to as the FTJ in a few outposts of the industry 16 years after we changed the title from the Fruit Trades Journal.

As publisher of the FPJ, Lockwood Press Ltd has, like many in the industry, struggled at times with the relentless and apparently never ending rationalisations brought on as the trade continues to evolve. These changes have led us to adapt and move with our readers, and thanks to the editorial direction under Tommy Leigthon, and advertising department succesfully led by Helen Armitage, we are more stongly placed than ever to face the future. It is our intention to build on that success going forwards, starting with this redesign.

I hope that you enjoy your new look FPJ. This is not the end of the process, and the next few months will see continued improvements and updates to the way we present what I hope you will agree is the industry’s freshest, most relevant news. Please send any thoughts and feedback you may have on our new look to me at justin@fpj.co.uk.