Last week, several journalists in the mainstream press revisited the story of Panama disease – the fungal infection also known as TR4 or Fusarium wilt that destroys banana plant roots – and the existential threat it poses to global production of Cavendish bananas. Inevitably, perhaps, given the mass media's hunger for stories with immediacy and instant impact that can support 24-hour news coverage, there are plenty of journalists out there who are happy to return every so often to the idea of a so-called #bananapocalypse (see also #avocalypse), the potential rapid destruction of the western world's commercial banana business resulting in the fruit's disappearance from supermarket shelves. Ever since Mike Peed raised awareness of what one Malaysian newspaper called 'the HIV of banana plantations' in his excellent 2011 piece for The New Yorker, news of the impending implosion of our banana supply has been 'about to happen'. In late 2013, Nature reported that TR4 had been found in Mozambique and Jordan, raising fears it could spread to major producers and decimate supplies; the following March, it was a 'lumbering goliath' on the move towards Latin America; last December, Michael Ford told The Grow Network that the bananapocalypse was indeed coming; and then just last month, experts attending the International Banana Congress in Miami were reported by The Guardian as racing to stop that same disaster.

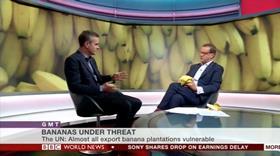

On Monday, I was at New Broadcasting House to speak to BBC World News about bananas and the threat from Panama disease. Of course, I'm not denying there's a threat or that Cavendish might be wiped out. If TR4 does spread to Latin America, that's a massive problem, especially when you consider that the continent is responsible for supplying most of the bananas that are sold in Europe and North America. But I also hear lots of talk about the problem being overstated. One person I spoke to this week – a former employee of Chiquita, no less – implied that researchers have exaggerated the risk posed by Panama disease in order to secure funding for their work. Even if that is true, I'm not convinced it rules out the possibility that the outbreak could consign Cavendish to the same fate as its predecessor, Gros Michel. So, as I waited for the BBC's World News anchorman Aaron Heslehurst to finish his mouthful of banana and hit me with his first question, I was determined to offer a balanced viewpoint that represented the reality of the situation: yes, Panama disease is a problem and one the banana trade would clearly prefer did not spread to Latin America, but so far it has also been a slow-moving problem; it's also something the industry is now spending more time and money on attempting to solve.

Admittedly, I don't have all the science to hand, but it seems odd that urgent warnings about the rapid disappearance of bananas from our supermarket shelves have been published many times over the past decade, and yet they're still there, selling by the truckload. There's a scene in the original Austin Powers film where a security guard is run over by a steam-roller moving no faster than snail's pace, and that's what the spread of Panama disease seems like to me. All the banana business needs to do is make sure it steps out of the way in time. But surely it's a battle that will play out a period of several years, rather than days or months?

Fruitnet's Latin America editor Maura Maxwell was in Miami last week to attend the International Banana Congress organised by Corbana and Acorbat. She told me on her return that no-one in the banana sector appears to be underestimating the risks associated with the soil-borne fungus; on the contrary, investments in research already show signs of yielding solutions, such as a more resistant strain of Cavendish that can be used to replace affected plantations. Bananapocalypse, bananageddon, call this banana drama what you will; but remember, TR4's spread hasn't exactly been at the same speed as our modern-day media moves from story to story. It's a far more nuanced situation: yes, the world is a much more inter-connected place than it was when the market dominance of Gros Michel was torpedoed by an earlier strain of Panama disease during the first half of the twentieth century, and this means diseases will probably spread further and quicker; but it's also true to say that the banana industry is far better placed to tackle, and overcome, the challenge it faces. Only time will tell if it has done enough in time to save its own skin.