Suddenly the global food business is alive to the consequences of the ongoing surge in food prices: in recent weeks it has caused among many other things the collapse of the government of Haiti, a rice export ban in Thailand and the introduction of rationing at Wal-Mart stores across the US.

Dire warnings about the impact of the recent triple-digit percentage rise in the price of key foods such as rice and wheat have now become the staples of global organisations and national governments.

The Food & Agriculture Organisation has warned about the dangers of starvation across parts of the developing world while the UN's Food Programme has set up a task force to tackle the shortages. Even France's farm minister Michel Barnier has weighed in with his solution, pleading for the preservation of the EU's Common Agricultural Policy which, in his opinion, will bring about greater price stability and more reliable supplies of food. Indeed, Monsieur Barnier reckons other regions should learn from the EU and adopt the same policy mechanism.

Others believe that soaring food prices should cause us to revise our attitudes to hotly contested issues such as GMOs, while the organic lobby says its system of agriculture is the real panacea to solve what has become a systemic problem of global food shortages.

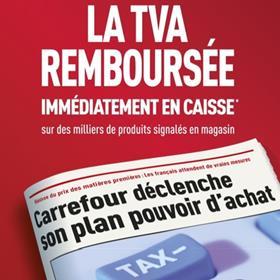

Rising prices are making themselves felt elsewhere too. Carrefour, the leading French food retailer, last month launched a new price-based promotion during which it promises to pay back the value-added tax that has been added to the end of shoppers’ till receipts.

Carrefour's Pouvoir d'Achat campaign, which includes fresh fruit in a basket of food items that benefit from the cash-back guarantee, is also motivated by the food retailer's need to defend its market share. Like others, it has been caught napping both by the sharp rise in sales enjoyed by France's hard discounters and recent consumer polling that shows French shoppers plan drastically to tighten their belts in future.

The trend is replicated elsewhere in Europe. We know already that many Italians don't earn enough in their paypackets to see them through to the end of the month, but it still comes as a shock to read front-page predictions in some UK newspapers of an £800-a-year rise (E1,000) in an average family’s grocery bill.

While fresh fruits and vegetables are in danger of being swept up in this price spiral that is also blowing across Europe, they haven’t been subject to the same spike in prices that we're now seeing in say the dairy or the cereals sector. No wonder the pasta-loving Italians and cheese-eating French are up in arms.

Indeed, the fresh fruit and vegetable category could become something of a refuge for penny-pinching shoppers who've started to buy on a budget. Produce prices are not rising across the board to the same extent as they are in other sectors, indeed in view of the absence of major shortages in the produce category it will not take much for shoppers to realise just what value-for-money fresh fruit and vegetables really represent. Out of this crisis there is perhaps also an opportunity.